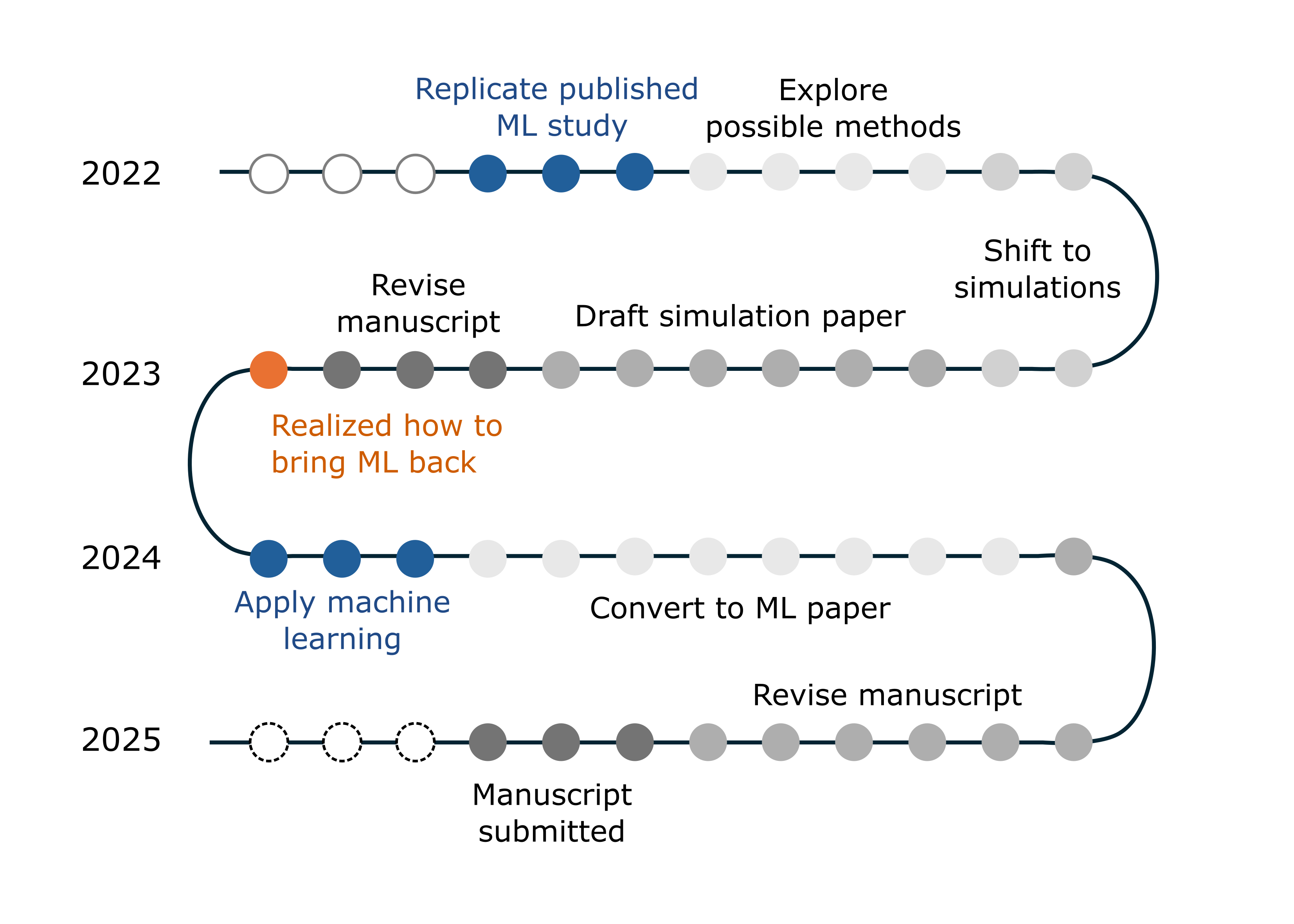

From a distant dream to reality - my AI4Science journey

Four years ago, doing a machine learning project felt like a distant dream. I didn’t know where to begin. Today, looking back at this long process, I want to share my journey of building an AI for Science (AI4Science) project completely from scratch.

Not your usual ML project

First, a disclaimer: this wasn’t the kind of deep learning project you’d typically see in a computer science department. I don’t have that kind of background or access to massive computational resources, nor do I aim to compete with people who build advanced algorithms. Their expertise is different, and often disconnected from science itself.

For me, the foundation has always been materials science. Machine learning is just another tool—a way to accelerate discovery, much like spectroscopy, simulations, or microscopy. The real goal is to solve a scientific problem, not to “do machine learning” for its own sake.

Replicating my first ML study

My AI4Science journey stretched across my entire PhD—nearly four years. We began with the idea of designing better 2D perovskites using machine learning.

(Quick explainer: perovskites are a rising star in solar energy materials. Some of them form 2D structures, where the atomic layers stack neatly like a sandwich. Others form non-2D structures, which are more disordered—imagine a Caesar salad instead of a sandwich.)

The initial spark came from a JACS paper by Yiying Wu’s group, where they used machine learning to identify design rules for whether these materials form 2D or non-2D structures. My supervisor sent me the paper, and I quickly tried to replicate their results. Within three months, I had succeeded. At that time, I felt a bit smug—“hah, machine learning is so easy!”

But I was wrong. Replication was straightforward because the method was already well-defined. The real challenge is choosing the right problem, defining meaningful input features, and picking target variables that matter scientifically. Originality is much harder.

When data runs out

We wanted to push further and explore a less investigated subset of 2D perovskites—the DJ phase. But when I tried applying the same machine learning approach, I ran into a wall.

The problem? Data. In the original study, they had about 86 data points from published experiments. For the DJ subset, I had only ~20—and the dataset was highly unbalanced. Machine learning simply wasn’t feasible.

So, reluctantly, I set aside ML and turned to another approach.

If not ML, then simulations

Since experimental data was scarce, we shifted to simulations to study the electronic structure of DJ perovskites (basically, how electrons behave inside the material, which determines whether it’s useful for devices).

This was another long journey: finding computational resources, learning how to run the simulations, troubleshooting countless errors, and finally producing meaningful results.

After more than half a year, I had my first full draft—a purely computational manuscript with no machine learning component. We spent another three months revising it, aiming for submission to PRL.

How ML found its way back

Then, just before Christmas, I stumbled across an interesting Nature Communications paper. It offered a clever way to scale up our dataset and translate material structures into features that could be understood by machine learning. Suddenly, I saw a way to bring ML back into the project.

Within three months, we had completely reframed the study. What began as a simulation paper became a materials science project enhanced by machine learning.

The long road to submission

Converting that simulation-focused draft into an ML-driven study took another eight months. Much of the time was spent digging deeper into the materials science side, asking whether the ML-predicted candidates could realistically be synthesized in the lab. Then came seven more months of back-and-forth revisions with my supervisor (unsurprising, since I was also finishing my thesis during this period).

We’ve faced one desk rejection, and now the manuscript is under review at another journal. Fingers crossed that it finds its home soon.

What AI4Science really takes

Looking back at the figure above, you’ll notice my takeaway for you: ML itself wasn’t the hard part. Once I had the right dataset, I could complete a full ML workflow in an afternoon. The real difficulty lay in understanding the scientific problem—deciding whether ML was the right tool, and preparing the dataset in a way that made sense scientifically.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: